* note: this is a longer version of the published article in Here Dongguan

China is obsessed with grueling entrance exams. They are promoted as a path to meritocracy, a level playing field on which everyone is measured by the same standards. The most notorious one is the gaokao, or the college entrance exam. Before that, there is one to enter high school, and another one to get into middle school. Exams can be taken too far, however, and a recent incident has created outrage, even for China standards. It happened in an exam to get from kindergarten to elementary school, something intrinsically ridiculous yet sadly, is the least absurd part of the story.

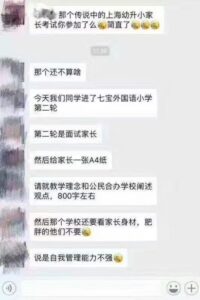

Officially, the Chinese government forbids “written or academic exams” to enter elementary school. However, that has never stopped schools from cleverly circumventing the rules. In early May, a few private elementary schools held entrance “interviews” for prospective students. It not only involved face-to-face interviews but also oral quizzes on Chinese, English, math, a talent demonstration, and a bewilderingly difficult test on a computer, which technically, is not a “written” exam.

If one were to accept the very notion of an entrance exam for elementary school, which many Chinese parents begrudgingly do, then this is simply a logical extreme of that concept, and not offensive in and of itself. What caused the outrage was not that the schools skirted the rules by de facto testing the kids, but by making a shocking move:

They tested the parents.

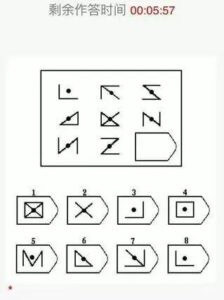

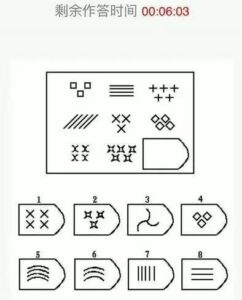

They gave parents logical puzzles like these to solve:

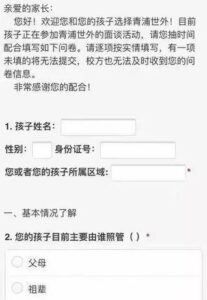

They asked about the education and socioeconomic background of the parents and the grandparents:

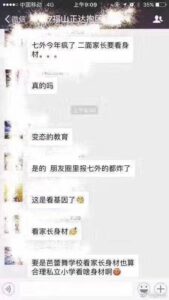

One school had the parents write an 800-word essay on the spot about education. Another went full Gattaca and allegedly didn’t accept the kids if the parents were fat, a practice with ugly implications:

These actions strongly suggest that admittance would be based on the child’s current ability and their predicted intellectual capacity, using the parents as a proxy. Most people feel disgusted and outraged about this practice. Yet, for something so deeply unsettling, it is surprisingly hard to articulate coherently what exactly is so offending.

The most common objection is that it is unfair to judge anyone based on circumstances out of their control. This is ironic because consciously or not, we have no problem judging beggars, criminals, poorly behaved children, celebrities, potential mates, and others constantly, based on limited information and a simplistic narrative. After all, it’s only discrimination if someone else does it; when we do it, it’s called insight.

All but the most naïve of us realize that given the same qualifications, people with certain traits will be favored, regardless of relevancy. Right or wrong, it’s reality. An interview serves far more than to understand the person; it also confirms and strengthens our biases, whether we care to admit it or not.

Allow me to ask this: Even if these schools did not openly test the parents, does anybody honestly believe that they would not discriminate behind closed doors? Is their crime simply quantifying what is socially taboo, and discriminating openly instead of covertly?

I believe what truly offends us is not just the garden-variety discrimination nor the brazenness of it. That’s a job for virtue signaling, and this feels very different. I think the reasons we experience such swift and intense disgust are more complicated and subtle.

We all have skeletons in our closets, and deep down we all feel inferior and insecure in one way or another. It’s part of the human condition. One reason we are offended is that by testing the parents and asking unsavory questions, the schools are exposing our own skeletons, laying bare the insecurities that we hold dear and close to our hearts.

Growing up we are taught that we can be the next Michael Jordan or Stephen Hawking, if only we worked hard enough. As we approach adulthood, we realize that simply isn’t the case. Given sufficient effort we can achieve competence, proficiency, and even expertise – but rarely greatness. You can’t will yourself to be 6’8”, no matter how hard you try. We mentally file it away with Santa Claus, and keep this depressing thought private, because it’s socially unacceptable to point out that the Emperor is naked. Ironically, we repeat this very same inspiring lie to our kids. And there it is – we are offended because the school is exposing our lies, imposing the unsavory realities of adulthood onto kindergartners, stripping them of whatever innocence remains.

It tells the rejected children that they are not only not good enough, but that they do not even have the capacity to be good enough. It finds them wanting instead of wanted, and implies that they are not merely incompatible, but defective. It is both humiliating and devastating, similar to what a heartbroken lover experiences – the agonizing realization that one can never be good enough. We resent that this undoubtedly adult emotion is unnecessarily forced upon a child; but more than that, we are deeply offended because it is ruthlessly honest, and even we, as grownups, are not adult enough to handle that kind of honesty, much less our children.

Ethics aside, there are rational reasons to reject this practice, even if legally permissible (they are for-profit private schools after all). An exam is only as good as its predictive value of future success, and it is doubtful that these exams are useful in that sense. Whatever limited insight one might glean from looking at parents’ traits, if any, seems far outweighed by the divisive and bigoted attitude it promotes. The message it sends to our children is reductionist and Darwinian, and is antithetical to the very purpose of education.

In many parts of Asia, schools are ranked solely by their graduating students’ test scores. This creates a perverse incentive. As school ranking becomes the ultimate end of education rather than preparing students for life in the real world, choosing students become like picking race horses; the student is neither the customer nor the product, but a substrate – breathing meat that delivers scores.

Our kids will shape the world to come, guided by the values we instill in them. If we want to arrive at a diverse and compassionate world, we shouldn’t start the journey with dehumanization and bigotry. The next generation deserves a better world even if we do not, and looking around, there is still a long way to go.